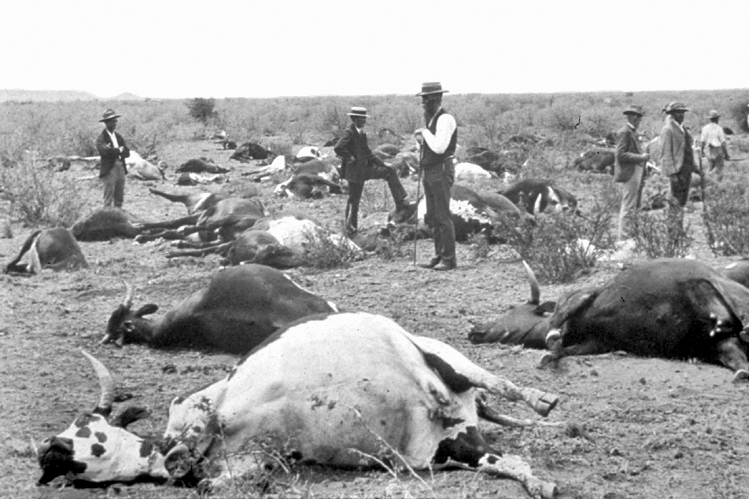

The Rinderpest epidemic of 1897 was one of the most devastating events in Namibia’s history, profoundly impacting its indigenous communities, especially the Herero and Nama peoples, whose economies and cultures were deeply intertwined with cattle. Often referred to as “cattle plague,” rinderpest is a highly contagious viral disease that primarily affects cattle, but can also infect other cloven-hoofed animals. The 1897 epidemic, however, was not just an agricultural crisis; it had significant socio-political consequences that would influence Namibia’s colonial history and the relationship between indigenous populations and European settlers.

In this article, we explore the Rinderpest epidemic of 1897, its causes, its devastating effects, and the long-term implications it had on Namibia’s socio-economic and political landscape.

1. Understanding Rinderpest and its Transmission

Rinderpest, caused by the rinderpest virus, is a contagious disease that primarily affects cattle, although other ruminant animals, such as buffalo, giraffes, and antelope, can also be infected. The disease is transmitted through contact with bodily fluids such as saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. Its symptoms include fever, discharge from the eyes and nose, and in severe cases, ulcers, diarrhea, and death.

The disease is particularly dangerous because of its rapid spread and high mortality rate among affected livestock. In regions where cattle are the backbone of agricultural economies, such as Namibia, rinderpest can have devastating economic consequences. Cattle, especially for the Herero, Nama, and other indigenous communities, were essential for trade, social status, and sustenance. The epidemic in 1897 would forever alter the course of these communities’ relationships with their land, cattle, and colonial authorities.

2. The Arrival of Rinderpest in Namibia

The rinderpest epidemic in Namibia is believed to have originated from the eastern parts of Africa, likely entering the country from the north or east through infected cattle. By the late 19th century, Namibia, under German colonial rule (as German South West Africa), had already seen increasing interactions with European settlers, traders, and missionaries. These interactions, along with the movement of cattle across borders, helped spread the disease rapidly.

While the epidemic of 1897 is the most well-known outbreak in Namibia, it is believed that rinderpest had been circulating in Southern Africa for several years, occasionally appearing in outbreaks. The 1897 epidemic, however, reached catastrophic proportions, overwhelming indigenous herders and farmers who were already dealing with the challenges of colonialism and settler expansion.

3. Devastating Impact on Indigenous Communities

For Namibia’s indigenous peoples, particularly the Herero and Nama, cattle were more than just livestock. Cattle played an integral role in their cultural and spiritual lives, representing wealth, social status, and ancestral ties. The loss of cattle had far-reaching consequences, including economic devastation and social disintegration.

The Herero were primarily pastoralists, and cattle were central to their livelihoods. They depended on their herds not only for food and transport but also as a means of exchange and a sign of wealth. For the Nama, cattle were similarly essential to their pastoral lifestyle. When rinderpest struck, it killed large numbers of cattle, and entire herds were decimated in some regions. It is estimated that up to 80% of the Herero’s cattle were lost during the epidemic.

The loss of cattle caused immense hardship. Communities were left with little means of sustenance, as cattle were vital for food, milk, and trade. The death of so many cattle also led to the collapse of social and economic structures that had been in place for centuries. Without cattle, many Herero and Nama were left destitute, forcing them to rely on other means of survival, such as agriculture, which was more limited in the arid environment of Namibia.

In addition to the direct economic consequences, the rinderpest epidemic had significant psychological and cultural impacts. For the Herero and Nama, the death of their cattle symbolized a devastating rupture in their cultural identity and traditional ways of life. The destruction of herds meant that long-held practices of cattle-based social organization were disrupted, leaving these communities vulnerable to further exploitation.

4. The Role of German Colonial Administration

While the epidemic devastated Namibia’s indigenous populations, the role of the German colonial administration in the spread of rinderpest remains a controversial topic. The Germans, who had been in control of Namibia since the Berlin Conference of 1884, were primarily concerned with expanding their influence and control over the land and its resources.

During the epidemic, the German colonial government did little to intervene in the spread of the disease. The lack of government action, combined with the mobility of cattle and traders across the region, allowed the epidemic to spread rapidly. Moreover, there were reports that German settlers, focused on preserving their own herds, were often more concerned with protecting their cattle than assisting indigenous populations whose cattle were suffering from the disease.

The German colonial administration’s indifference to the rinderpest epidemic played a role in the immense suffering experienced by the Herero and Nama. This neglect added to the growing resentment of colonial rule, which was already marked by exploitative land policies, forced labor, and racial discrimination.

5. The Aftermath: Long-Term Effects on Namibia’s Indigenous Populations

The rinderpest epidemic of 1897 not only devastated Namibia’s indigenous cattle economy but also significantly weakened the resistance of indigenous communities to German colonial rule. The collapse of the Herero and Nama cattle economies left these groups vulnerable to further exploitation, displacement, and eventual military conquest.

In the years following the rinderpest epidemic, the Herero and Nama faced increasing pressure from the German colonial authorities to accept German rule. The loss of cattle further eroded their ability to resist German encroachment on their land, and by 1904, the Herero launched an armed revolt against the German settlers and colonial government. The resulting conflict, the Herero and Nama War (1904-1908), was marked by brutal reprisals from the Germans, including the infamous genocide of the Herero people, in which tens of thousands were killed, and survivors were sent to concentration camps.

The rinderpest epidemic of 1897, therefore, can be seen as a catalyst for a series of events that culminated in the brutal suppression of indigenous resistance in Namibia. By the time of the Herero and Nama genocide, the indigenous peoples were already weakened, economically and socially, by the effects of the epidemic, making them less able to fight against German oppression.

6. Legacy and Recognition of the Rinderpest Epidemic

The rinderpest epidemic of 1897 is one of the most significant events in Namibia’s colonial history, yet it is often overlooked in discussions about Namibia’s past. The long-term economic and social consequences of the epidemic were profound, reshaping the lives of Namibia’s indigenous peoples and contributing to their vulnerability in the face of German colonial expansion.

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in acknowledging the impact of the rinderpest epidemic. Scholars and historians are increasingly recognizing the epidemic as a key event in the broader context of Namibia’s colonial experience. Some see it as an early indicator of the brutal and exploitative nature of German colonial rule, which would later culminate in the genocide of the Herero and Nama.

Today, there is an ongoing movement in Namibia to demand reparations and recognition of the injustices committed during the colonial period, including the devastation wrought by the rinderpest epidemic. While it is impossible to undo the damage caused by the epidemic, the recognition of its impact is an important step in addressing Namibia’s colonial legacy.

The Rinderpest epidemic of 1897 was a defining moment in Namibia’s history, changing the lives of the Herero and Nama peoples and accelerating their subjugation under German colonial rule. The loss of cattle, which were central to these communities’ economies and cultures, dealt a devastating blow to their way of life. The epidemic’s consequences were not just economic, but deeply cultural and psychological, causing lasting trauma to Namibia’s indigenous peoples.

While the epidemic may not be as widely discussed as other events in Namibia’s colonial history, its effects reverberated throughout the country’s past. The epidemic weakened resistance to colonialism and set the stage for the Herero and Nama genocide. Today, the legacy of the 1897 rinderpest epidemic continues to shape the collective memory of Namibia’s indigenous communities and their ongoing struggle for recognition and justice.