Namibia’s journey to independence was shaped by a turbulent history marked by colonialism, resistance, and external domination. The transition from German colonization to South African mandate rule set the stage for decades of economic exploitation, land dispossession, and the resilience of Namibia’s indigenous people. This period is crucial for understanding the socio-political challenges Namibia faced and how these events shaped the nation’s eventual fight for sovereignty and equality.

The story begins in 1884 when Germany formally annexed Namibia, then known as South West Africa, during the Scramble for Africa. The Berlin Conference granted Germany control over the territory, giving rise to the colony of German South West Africa. Initially drawn by the promise of fertile land and mineral wealth, German settlers quickly moved to establish dominance. Indigenous communities, such as the Herero, Nama, Damara, and San, were displaced from their lands through treaties they were often coerced into signing or did not fully understand. As settlers established farms and mining operations, the local populations faced increasing restrictions on their traditional ways of life.

The turn of the 20th century brought mounting tensions between the colonial administration and the indigenous population. The Herero and Nama launched armed resistance in 1904 to reclaim their land and autonomy. This uprising was met with brutal force, culminating in the Herero and Namaqua Genocide. German forces, under the leadership of General Lothar von Trotha, implemented a scorched-earth policy, driving tens of thousands of Herero and Nama into the desert, where many succumbed to starvation and dehydration. Those who survived were sent to concentration camps, where they were subjected to forced labor under inhumane conditions. The genocide devastated the population and left a deep scar on the nation’s collective memory, becoming a rallying point in Namibia’s later independence movement.

By the time World War I began in 1914, German control over South West Africa was tenuous. South African forces, aligned with the British Empire, invaded the colony in 1915 and quickly defeated German troops. The end of the war saw Germany relinquish its overseas territories under the Treaty of Versailles. South West Africa was placed under the administration of South Africa in 1920 as a Class C Mandate of the League of Nations. The mandate system was intended to guide former colonies toward self-governance and development, but South Africa treated the territory as an extension of its own borders, imposing its domestic policies and laws.

Under South African rule, policies of racial segregation and land dispossession intensified. Indigenous Namibians were forcibly relocated to native reserves, which were overcrowded and lacked resources. The fertile land was allocated to white settlers, further marginalizing the majority population. The introduction of apartheid laws in South West Africa mirrored the racial hierarchy entrenched in South Africa. Indigenous people were denied political representation and faced restrictions on movement, labor rights, and access to education and healthcare.

The South African administration also sought to suppress resistance, but opposition movements began to take root. Early revolts, such as the Bondelswarts Rebellion of 1922, were met with military crackdowns, but they signaled the growing discontent among the local population. Over time, these uprisings evolved into organized political movements advocating for independence. The South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) and the South West Africa National Union (SWANU) emerged as key players in the fight for liberation, drawing inspiration from global anti-colonial struggles.

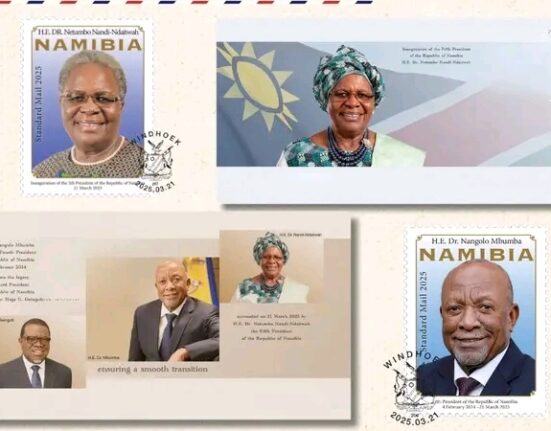

The end of World War II marked a significant shift in international attitudes toward colonialism. The League of Nations was dissolved and replaced by the United Nations (UN), which sought to promote self-determination and human rights. The UN formally terminated South Africa’s mandate in 1966, declaring its continued administration of Namibia illegal. However, South Africa refused to relinquish control, leading to a protracted struggle for independence. Namibia’s liberation movement gained momentum, with SWAPO leading a guerrilla war against South African forces and gaining international support.

The legacy of Namibia’s transition from German rule to South African mandate is still felt today. The policies of land dispossession, economic exploitation, and racial segregation left deep inequalities that Namibia continues to address. However, this history also fostered a strong sense of national identity and resilience among its people. The struggle for self-determination became a unifying force, culminating in Namibia’s independence in 1990.

Today, Namibia stands as a testament to the resilience of its people and their determination to overcome a legacy of oppression. Efforts to address historical injustices, such as land reform and economic empowerment, remain central to the nation’s development. Namibia’s history serves as a reminder of the importance of acknowledging past struggles and working toward a more equitable and inclusive future.

Join 'Namibia Today' WhatsApp Channel

Get the breaking news in Namibia — direct to your WhatsApp.

CLICK HERE TO JOIN